Are we, Jasper, the artistic stewards of this place? Are we working to preserve its flavor, its mechanisms, its language and natural history as we make our way across the trails and pastures, hoofbeat after hoofbeat? Are we behaving as Wendell Berry says we should?

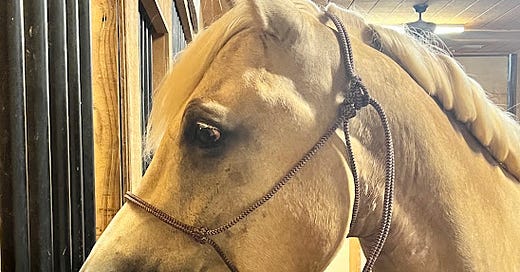

Jasper answers this by reaching for a hickory branch, then skittering away quickly when he hears it snap back. He’s making his own troubles out here on the trail.

Look, I say, all those birds! Let’s name them. Red winged blackbirds, mockingbirds, bluebirds, red-headed woodpeckers, all flitting about a big pile of branches and tree debris, all fluttering and flapping around us. We’re riding in the morning, with the worm-catching early birds, still the sun blazes unbearably outside this canopy of trees.

We make our way to one watery spot, low and lush, dank and dark. There are beautiful elephant ears growing in one of the wettest parts, right out of the oozing, black mud. Non-native, invasive. Those words taint my appreciation of their beauty.

Jasper does not concern himself with elephant ears. He has spotted the cows standing clustered at the edge of the woods, right where this summer morning’s white light breaks through and dazzles the cows who shine like obsidian, like polished copper.

I am lucky, Jasper. I am lucky beyond measure. To spot the cows in the morning light, from the back of a horse, on a farm with hundreds of acres of ridable land, miles of trails, sweet hills of Alabama’s piedmont with its trickling streams, river rocks, red dirt, pines and oaks and deer and turkeys, the smell of a sweaty horse, the snort and stomp and shuffle and step under my body, the morning already too hot for riding, the day just arriving and I’ve already been to the highest holy ground I know.

This is my place poem, this is my place.